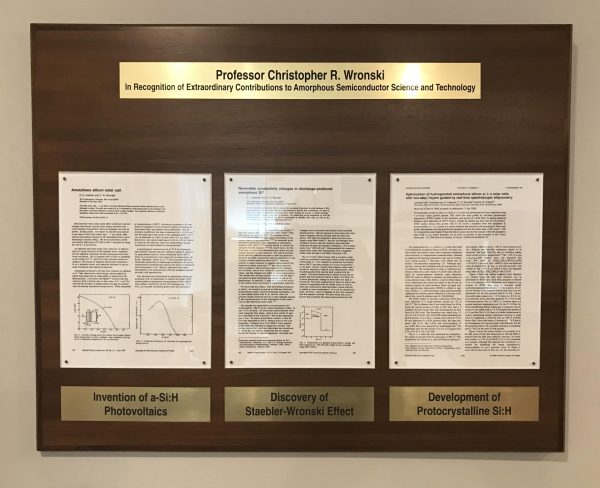

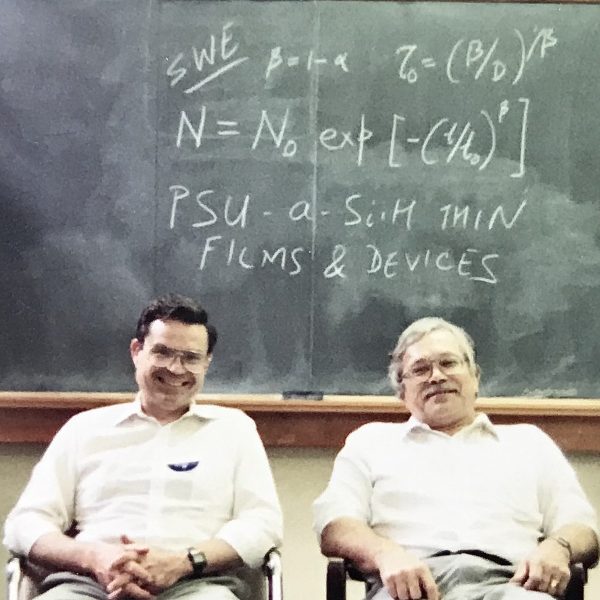

This is the second part of a two part series about the work of a research team that included Professor Christopher Wronski of the Penn State University Engineering Department. The narrative continues with Dr. David Staebler’s first hand account of their discovery. Staebler is the scientist that worked jointly with Wronski on discovering the measurable characteristics of amorphous silicon that became a major milestone in furthering development of the global solar industry.

David Staebler emphasized what he remembered about Dave Carlson.

“Dave Carlson encouraged us to work together and to publish quickly,” he said.

Staebler had just returned in late 1975, from a one year stay in Brazil as a visiting professor at the Universidade de Sao Paulo. He had just met Carlson and Wronski. Staebler was looking for his next project. He was looking for new materials. Although Staebler’s research focus was material for optical storage, Dave Carlson suggested he look at the electronic properties of the amorphous silicon that Carlson and Wronski had just discovered. All three engineers

were employed at the David Sarnoff Research Center, then RCA Laboratories. Staebler still had the appropriate testing equipment from his previous research on insulators. He had no luck in examining the new material that Carlson and Wronski had given him for practical solutions for optical storage uses.

The following narrative is from Staebler’s presentation to the Materials Research Society Symposium in 1997, a 20 year historical commemorative of the Solar Industry. Staebler documents how the Staebler/Wronski Effect just happened and happened quickly.

“So I started on the conductivity measurements of a -Si:H (amorphous silicon) sample. My samples came from Chris, who had already started making many photoconductivity measurements, and kept some of his samples on the window sill in his room. My job was to measure the temperature dependence of the dark conductivity to compare the activation energy to expected values from the band gap. I used my simple hot plate with 4 probe contacts, left over from my electrochromic measurements on Strontium Niobate.”

Professor Staebler mentions a humorous part about the discovery.

“I honestly can’t remember the

moment when I realized that there was something funny going on, but Chris

remembers I accused him (jokingly I’m sure) that he couldn’t measure these

samples right. My room temperature data was different from his. Plus,

they were all over the place, with no clear cause and effect, as were the data

in the literature. The more the puzzle remained, the more we tried to

figure it out.”

Staebler’s background in photo-chromatics and hologram storage sped up their discovery process.

“Both these effects were caused by light that generated electrons in the conduction band. When the electrons were re-trapped in new defect sites, a change occurred (either a new absorption, or an electric field). When you then heated the materials, the electrons returned to their thermally stable defect sites and distribution. Thus the optically induced state was metastable, and the changes were completely reversible.”

His prior experience did not help much in finding a mechanism, but it did help for their testing and realization process.

“The parallel is obvious. We saw that a-Si:H (amorphous silicon sample) film conductivity went up when we heated it above 150 degrees C on my hot plate during a temperature-dependent-conductivity measurement. We found that it did not change in the dark, but if we left it back in the sunlight (on Chris’s window ledge) its dark conductivity could go down by more than 4 orders of magnitude. After a flurry of tries and tests, we felt that we could reproduce this effect of many samples. We had a real, thermally reversible, optically induced effect. At that point, we carried out a number of experiments over many months trying to find out the specific mechanism.”

Both research scientists were guided by the expertise of Dave Carlson to publish their research as soon as possible, even if incomplete. The first manuscript was published in August 15 issue of “Applied Physics Letters.” Their next paper was published three years later. Their conclusion was that a localized defect undergoes a metastable change while trapping or acting as a center for recombining photo-generated charge carriers in extended states.

“Through all of the last 20 years, cell and module performance has continually improved to the point where it is a successful product, and with a growing market. Perhaps this is the best of all possible world: a continuing market for a-Si:H(amorphous silicon) cells, and thus a continuing interest in improving them and funding to help do it. Who could ask for more?”

David Staebler’s question from 25 years ago left the door open for even more development into the solar industry and markets for today and the future. A team of scientists shared their work efforts and continued working from new ideas, and measurable observations.

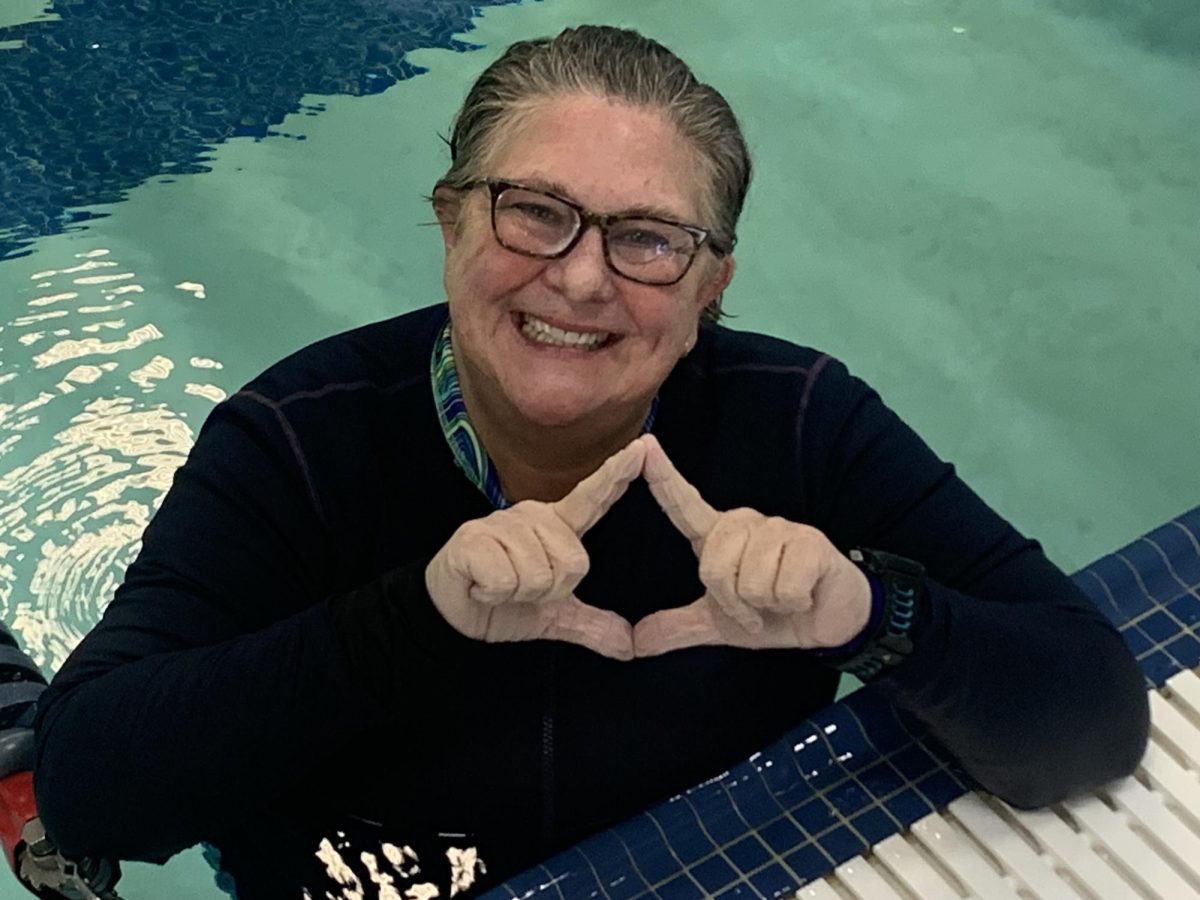

Christopher Wronski, Professor Emeritus-Penn State University, died in 2017. David Carlson PHD- Rutgers University, died on October 15, 2019. David Staebler, PHD Princeton University, is living in the Susquehanna Valley, in fact, not very far from the Harrisburg campus. According to Google scholar, the Staebler/Wronski Effect research paper from 1977 is still being cited by scientists and electrical engineers in ongoing research into 2024.

The successive research and work efforts of these three scientists contributed to further development of the solar industry from earlier research of glow discharge deposition processes that had already been accomplished previously by earlier research scientists. Successive work efforts by many scientists working independently or in teams shared different research and communicated with one another in meetings, and on the internet. Over just a 50 year period a totally new product developed further into the global solar industry.

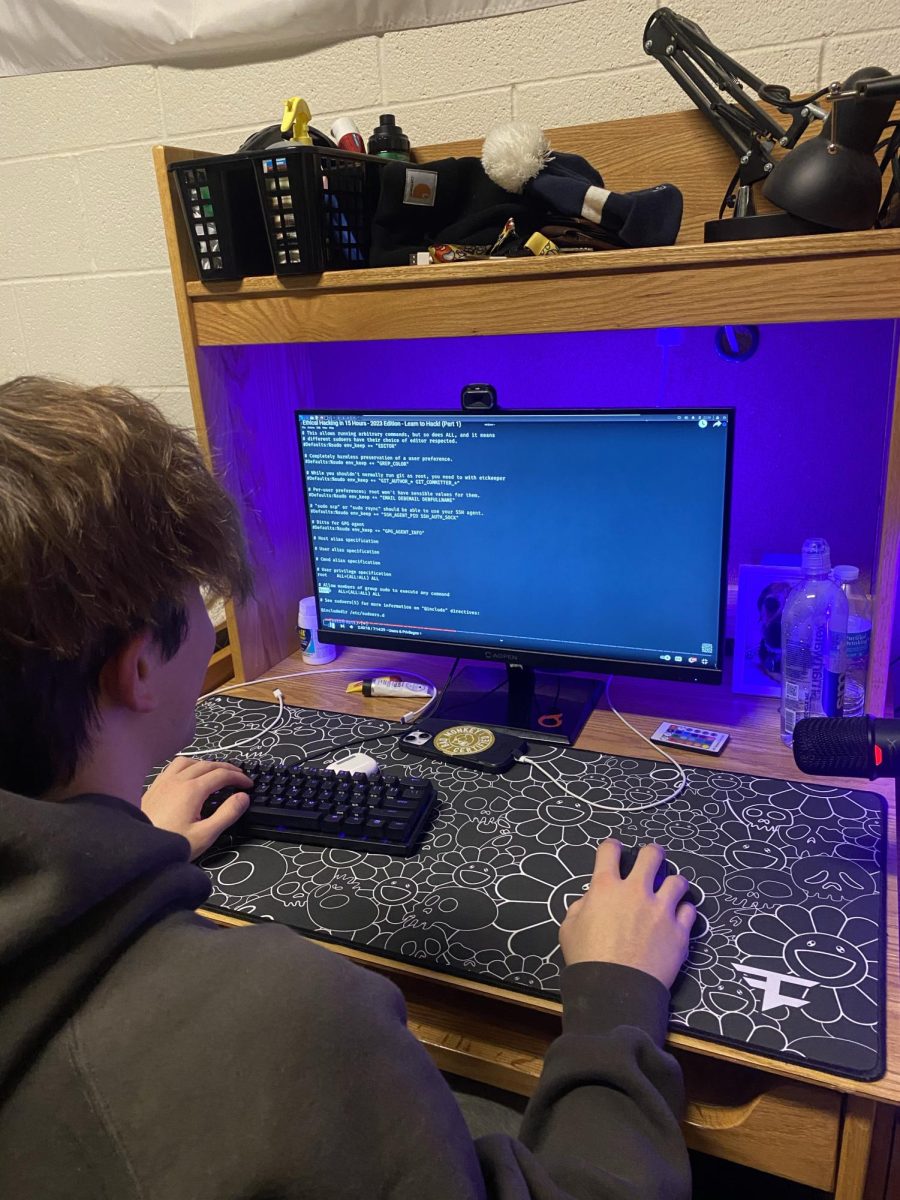

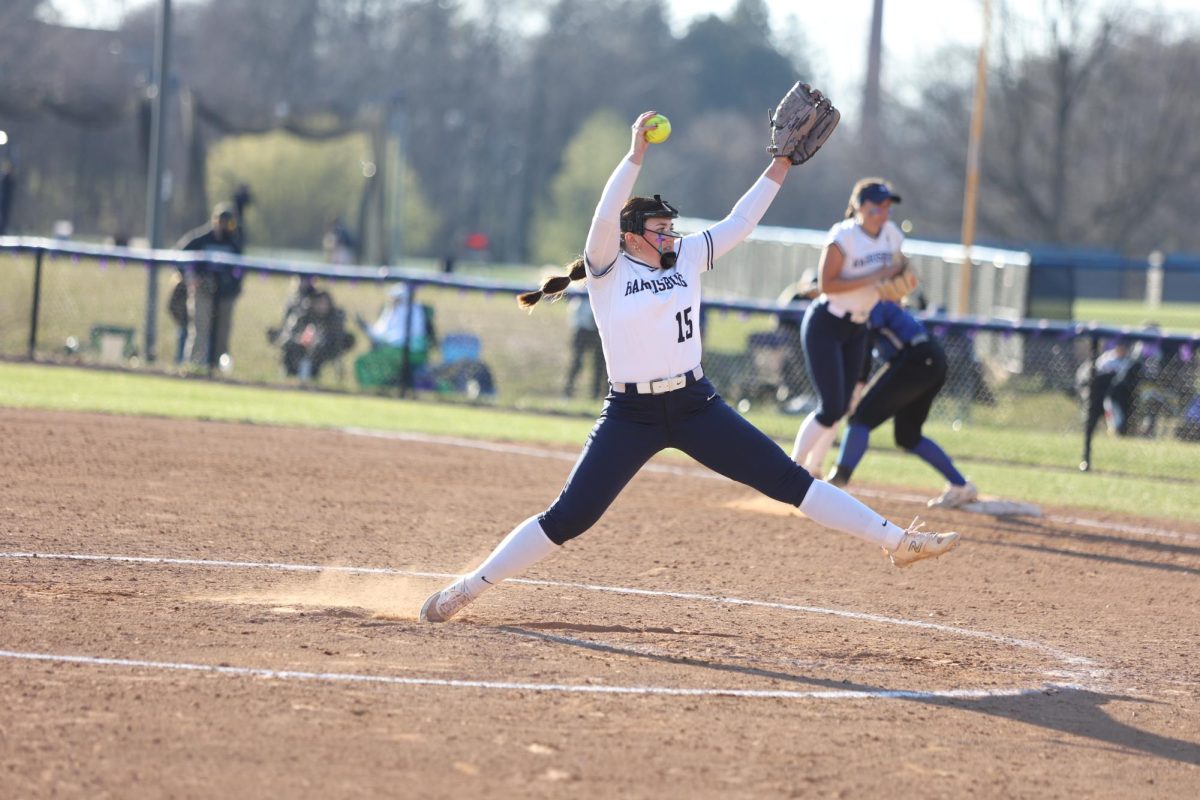

A little bit more than something funny was, and is still going on. Instructors and students from

Penn State University have contributed and continue to contribute to science and industry.

That kind of work effort is a continuing day-by-day real successful process, even with the up-and-down days.